July’s Fungi Focus: Ash Dieback (Hymenoscyphus fraxineus)

Members of the kingdom of the fungi can essentially be divided into the two basic categories of basidiomycetes and ascomycetes. The basidiomycetes form and release their spores on specialised cells called basidia, which can be found on the underside gills of our more familiar mushroom and toadstool-shaped types, or within the pores of boletes and brackets and suchlike.

Ascomycetes, however, produce their spores in the elongated cells known as asci that cover their spore releasing surface. Each individual ascus can contain usually around 8 spores, like snooker balls in a sock, which then get released out of the end when ready: the word is derived from the Greek for wineskin or sac. Typically we might think of cup fungi, such as the various members of the Peziza genus, like the Blistered Cup (Peziza vesiculosa) depicted here, whose favoured substrates of well-rotted manure or compost heaps lends has led to its alternate common name of the Common Dung Cup.

Blistered Cup, Peziza vesiculosa

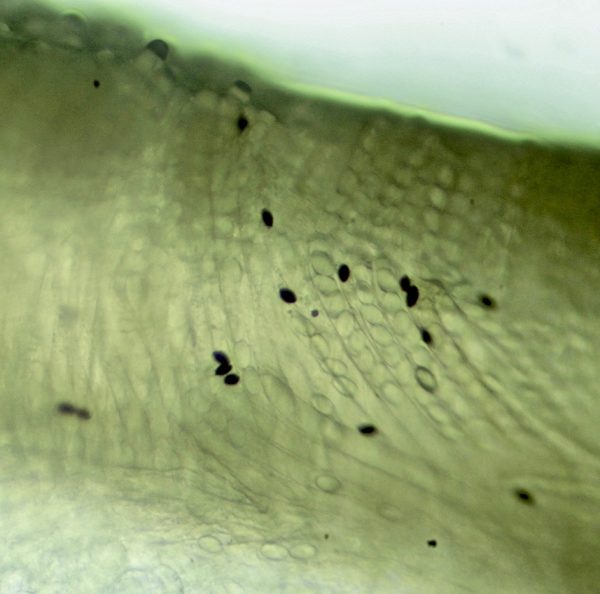

It is important to remember here that the cup itself is not the ‘ascus’, but contains within its surface a multitude of these sacks that can only be seen under the microscope. In other words, it is these microscopic details, not the visible macro features, that define whether a given fungi is characterised as being basidiomycetes and ascomycetes. So basidiomycetes encompass much more than cap-and-stem mushrooms and brackets, and include not only the gasteroids or puffballs and the resupinates or crust fungi, but also less obvious examples like the rust fungi that are prevalent as vivid orange powdery coatings or blotches on living leaves and stems during our late-Spring and Summer months (more on these next month!)

Microscope X-section of a Blistered Cup, showing the asci containing the spores

Ascomycetes constitute a far larger phylum within the fungi kingdom than basidiomycetes. Aside from the obvious cup fungi like the numerous Peziza species and such striking relations as the Green Elf Cup (Chlorociboria aeruginascens), Scarlet Elf Cap (Sarcoscypha coccinea), or Orange Cup (Melastiza chateri), we have the hard black Xylaria genus consisting of such common finds as King Alfred’s Cakes (Daldinia concentrica) , Candlesnuff Fungus (Xylaria hypoxylon) and Dead Man’s Fingers (Xylaria polymorpha), and the black blotches known as Tar Spots (Rhytisma acerinum) that begin blemishing the leaves of sycamores and maples around this time of year.

Orange Cup (Melastiza chateri)

But it is certainly never obvious to the naked eye to which class they belong. Jelly Ears might bare superficial resemblance to Orange Peel Fungus (Aleuria aurantia), for example, but they are basidiomycetes whereas the latter are ascomycetes. The various larger jelly fungi commonly referred to as Witches Butter, which include the black Exidia nigricans and the Yellow Brain (Tremella mesenterica) are basidiomycetes, while the similarly brain-like Purple Jellydisc (Ascocoryne sarcoides) are ascomycetes. As mentioned, rust fungi are basidiomycetes, but the Erysiphaceae fungi that cause powdery mildew are ascomycetes.

Indeed, ascomycetes present a frustratingly difficult field of study for the amateur naturalist, even more so than the crust fungi. The most comprehensive entry-level book devoted to the study, Peter. I. Thompson’s Ascomycetes in Colour: Found and Photographed in Mainland Britain (2013) features 700 species out of the estimated 64,000 found worldwide, but a flick through its pages reveals the depressing truth that most are little more to the naked eye than small black blotches or variously coloured jelly-like disks or cups less than a millimetre in diameter.

The mollisia genus, for example, consists of 121 separate species (according to Wikipedia). Technically speaking, only the most commonly found of these, Mollisia cinerea, has an English name, the Common Grey Disco, but presumably Grey Disco could be just as applicable to the other 120, each differentiated by their specific host on which they are found (various pieces of dead wood, reeds or grasses) but mainly by microscopic details such as the dimensions of their spores, asci sacs or “paraphyses” (according to the book, the “infertile cellular structures which grow between asci”).

Common Grey Disco (Mollisia cinerea)

There are also, among the ascomycetes, many species possessing a shape that would seem to situate them among our more familiar fungi finds from the basidiomycetes – and a tastiness too, notably the morels. But did you know that DNA sequencing has now revealed over 70 species in the Morchella genus of true morels alone?

It is all enough to make those of us who like to pinpoint their finds precisely throw up our hands in despair at the enormity and complexity of the natural world. But ultimately how much does it really matter if the tiny grey disks growing on a tree stump at the bottom of the garden are Mollisia caespiticia rather than Mollisia fusca? And might some of these simply be considered “rarer” than others simply because the vast majority of people have neither the time, knowledge, inclination or resources to subject their finds to such painstaking scrutiny?

Well, there’s at least one species that has appeared over the past decade that has highlighted the pressing need for more mycologists with microscopes and molecular phylogenetic skills across the world. It is also the reason why I’ve decided to change the title of these blog postings from ‘Monthly Mushroom’ to ‘Fungi Focus’. The word ‘Mushroom’ seems to more hint at certain types of fungi that are either more or edible or at least conspicuous than the average. Hymenoscyphus fraxineus is neither of these things. In fact, it is an altogether undesirable addition to the wider European ecosystem all round.

Hymenoscyphus sp.

The Hymenoscyphus are a genus of tiny ascomycetes that, until you get really close up, look like your basic mushroom. Most are white to pale cream or pale brown when dry and look like a nail or funnel growing from their specific substrate, except that the spores are released from the asci on the top rather than basidia cells on a gilled underside. The 150 or so species vary in terms of the more visible dimensions of relative stem length, cap diameter, colouration, and can also be differentiated to some extent by their host substrate. The Nut Disco (Hymenoscyphus fructigenus), for example, grows on old nutshells, acorns or beechmast.

Hymenoscyphus albidus and Hymenoscyphus fraxineus both look essentially identical, their fruiting bodies proliferating across the fallen stalks and midribs of the distinctively shaped compound leaves of the ash tree (the ‘petioles’ and ‘rachis’) as tiny white funnels with a cap diameter of a maximum of 3mm, usually smaller. Their stems are blackened at the base where they emerge from the substrate, and indeed, it is the fungus itself that is responsible for the blackening of these tiny twigs. The two species can only really be distinguished from one another by minute microscopic details at the cellular level, and for a while the second type was known as Hymenoscyphus pseudoalbinus.

There is a slight darkening at the base of the stem where it emerges from the blackened dead ash petioles

The crucial difference is that while the former is a native fungus that does no harm to its host, the latter, only described scientifically described in 2006 under the name Chalara fraxinea and first identified in the UK in February 2012, is the pathogenic fungi responsible for the widely reported ash dieback disease.

An academic paper published in the journal Mycology in 2014 describes H. albidus as “rather uncommon”, although for the numerous reasons already mentioned above, one might assume that historically this and so many other tiny ascomycetes of its ilk might well have passed by unnoticed.

There has been considerable more attention on recording its considerably more destructive non-native relative in recent years, to the extent that a Defra project involving Fera, Natural Resources Wales and the Forestry Commission has produced an interactive online map detailing its spread across the UK.

Hymenoscyphus

Now I have neither the patience or the microscopy skills to take a paper-thin cross section of a fungi just a couple of millimetres in diameter (considerably smaller when its dried out!) and squash it beneath a microscope cover slide to locate its distinguishing details. I think it is safe to assume however, that my two findings over the past month - one in a patch of woodland near Canterbury, the other outside Bradford-on-Avon - that have provided the photographic basis for this article, were of this foreign interloper, rather than the “rather uncommon” native, and if so, its prevalence is quite alarming.

A 2018 paper in Forestry An International Journal of Forest Research reports that the earliest records of the ash dieback fungus were on the “eastern seaboard of Kent, East Anglia and sporadically in Lincolnshire and East Yorkshire northwards to Northumberland and Scotland”, as indeed is clear from the interactive map, and that this “suggested the possibility of disease establishment as a result of spore inoculum blown in the wind from continental Europe”, across which the epidemic had spread from the first reports of ash dieback in Poland and Lithuania in the early 1990s.

A 2018 paper in Forestry An International Journal of Forest Research reports that the earliest records of the ash dieback fungus were on the “eastern seaboard of Kent, East Anglia and sporadically in Lincolnshire and East Yorkshire northwards to Northumberland and Scotland”, as indeed is clear from the interactive map, and that this “suggested the possibility of disease establishment as a result of spore inoculum blown in the wind from continental Europe”, across which the epidemic had spread from the first reports of ash dieback in Poland and Lithuania in the early 1990s.

However, the authors argue that there is now evidence that Hymenoscyphus fraxineus was already present in England long before 2012, on imported nursery trees, and “that planting of infected H. fraxineus tree stock in England could date back to the early 1990s, with affected trees dying in the mid-2000s.”

The fungus is not of European origin, however, and has now been identified as originating from East Asia, where it associates with native ash species such as the Manchurian Ash (Fraxinus mandshurica) in Russia, China, Korea and Japan, to which it does no harm at all. On our European or Common Ash, Fraxinus excelsior, the spores first affect the leaves, with the fungus hyphae then growing to infect the petioles and creeping along the branches, constricting their vascular flow so that they die and drop off and eventually the crown dies back. In most cases the tree ends up killed off entirely. The tiny fruiting bodies that spout up on the infected petioles among the fallen leaf litter provide visible evidence of the fungal presence, and appear in the warmer months. It is these from which the spores are released, spores that can drift over an alarmingly large area.

Tragically there seems to be no way of controlling the march of this devastating fungi, and Hymenoscyphus fraxineus amongst the forest litter looks set to become an increasingly common sight throughout future summers. Nature abhors a vacuum, of course, and indeed a more recent article in the Forestry journal discusses how our native Common Ash looks likely to be replaced by the natural growth of other species such as sycamore or beech. Sycamore is a tree that proves remarkably resilient to fungal attack, which in this context is a good thing, but sadly for the mushroom freaks among us, also fungal symbiosis. As Pat O’Reilly writes in his wonderful Fascinated by Fungi, “sycamore woodland in autumn can look like a mycological desert… from a fungi foray point of view, Sycamores are boring.”

There are a few carrots of hope in all this. For a start, the virulence might have been slightly overplayed by the media in the sense that the fungus does take quite some time to completely kill off the tree, and clearly from an evolutionary point of view, it wouldn’t make sense for it to destroy its host plant off completely. Furthermore, there is evidence of a genetic resistance among a small proportion of individual Common Ash specimens, so it is likely we won’t be losing our entire population of this native tree.

Sadly our already rare harmless native Hymenoscyphus albidus is likely to be outcompeted by its destructive Asian counterpart in terms of retaining its specialist environmental niche within the leaves and petioles of a dwindling European ash population, although one imagines there will be few who will ever notice its disappearance.

As the influential father of biodiversity E. O. Wilson famously observed, “It’s the little things that run the Earth.” His own sphere of expertise was insect life, but the comment is no less pertinent to fungi, nor indeed any aspect of the natural world.

Hymenoscyphus fraxineus is here to stay in the UK for sure, and there is nothing any of us can do about it. The ability to recognise it, however, should at least bring home the importance of looking more carefully at things like ascomycetes and other fungi as symptoms of an imbalance caused by climate change, the cross-species contamination due to the global trafficking of plants and other human activities.

Hymenoscyphus fraxineus is here to stay in the UK for sure, and there is nothing any of us can do about it. The ability to recognise it, however, should at least bring home the importance of looking more carefully at things like ascomycetes and other fungi as symptoms of an imbalance caused by climate change, the cross-species contamination due to the global trafficking of plants and other human activities.

Comments are closed for this post.

Discussion

I’m not sure anyone has ever tried eating this before – they’re around a millimetre in diameter, so I doubt you’d ever get enough even for it to register a taste.

Whether it’s harmful to humans or not, I don’t think is on record!

as a side issue and possible benefit can one eat it? i recoginse that it would take a lot of fruitng bodies to bolster my morning bacon!

Good summary – thanks

Very useful and informative but my pedantry alarm went into overdrive.

There’s no such thing as a fungi. It’s a FUNGUS! Oddly, I don’t mind “funguses” as a plural, but ‘fungi’ is just plain wrong. Unless there are lots. It’s also usually an ugly sounding word, depending what follows it (‘a fungi is…’ is a horrible usage.)

Please, do away with it. What would Fungi the Bogeyman say?

Jerry

24 November, 2022