March’s Fungi Focus: Wet Rot and Fawn Starweb

There is not a lot of love for resupinate or crust fungi even amongst fungi specialists, yet alone the wider community of naturalists and nature recorders. I’ve outlined some of the reasons why this might be so in my previous postings on Hairy Curtain Crusts, Elder Whitewash, and Cinnamon Porecrusts – these are mainly related to their inedibility and difficulty in identifying them. However, in last month’s focus on Antrodia carbonica, I did hint at why one might, perhaps even should, develop an interest in the subject, or at least an awareness – especially if you are an arborist, builder or anyone else who deals with wood or timber for a living.

I remember an occasion shortly after I first started dipping my toes into the subject, when I found a striking example of a corticioid fungus (i.e. possessing a smooth surface, without pores) on one of the trees in an avenue of cypresses stretching alongside a public right of way through farmland. The bulk of the crust that spread thinly across the bark of its host was white, with a distinctive cobwebby margin. However, the areas to the centre were a lot thicker, and had begun developing a knobbly surface with a garish olive green tinge, although the flesh in general was flimsy and insubstantial, making it difficult to peel off the tree without removing the bark.

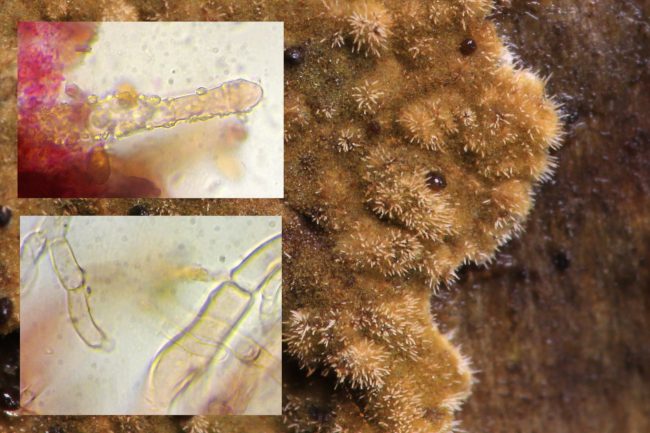

Coniophora puteana or Wet Rot fungus developing on the bark of a cypress tree

I took a small piece home to begin the microscopic scrutiny that such fungi usually require for identification. There are a number of features that one really needs to look for when dealing with some of these tricky resupinate specimens, but spores are a good place to start. And so I laid a section face down on a microscope slide and several hours later was able to note that the spores were brownish, ovoid, thick-walled and a relatively large 10-13x6-8 microns [µ) in size. A thin cross section also revealed that the septa, the separating wall between the individual hyphae cells that comprise all fungi, was of the variety described by mycologists as simple – a clean division as opposed to the clamps one sees in a number of other species.

Wet Rot fungus with microscopic details showing the simple septa in the hyphae that make up its body and the ovoid spores

All of this evidence was enough for me to pinpoint, with the aid of Hugill and Lucas’ invaluable ‘The Resupinates of Hampshire’ book and their even more essential online key, that what I had found was Coniophora puteana. I Googled around to find out a bit more about it and was shocked when the first words that came up were ‘Wet Rot fungus’. Not only is this particular species widespread enough to warrant an English common name, but the name in question also draws attention to the potentially devastating effect that, should any of my spores have got in the wrong place, it might wreak on my own roof timbers. Rather than fling the finished sample out into the garden as I usually do after I finish examining them, I immediately burnt it. (I had a similar reaction when I first identified the tiny white cups of Hymenoscyphus fraxineus and realised that this was the fungus responsible for Ash Dieback disease – I destroyed my sample in case I inadvertently managed to unleash any spores that might float towards any ash trees in my vicinity).

The close relative of the Wet Rot fungi Coniophora olivacea growing with Crimped Gills on a rotten birch log.

I usually find that once I’ve managed to identify a species with such a degree of certainty under a microscope, they become readily recognisable in the field. Indeed, the Wet Rot fungus is pretty distinctive once one gets to know ones crusts, and most roofers and builders whose job it is to know the cause of household structural damage would spot it instantly without recourse to a microscope.

In the wild, one should note, that the presence of Coniophora puteana on living coniferous (and occasionally deciduous) trees doesn’t signal that its host is doomed, although some more overzealous arborists paid to remove “diseased” trees from municipal or private land might tell you otherwise. The fungus itself plays its own role in breaking down the dead wood on the tree, and it is only if the tree itself is stressed for other reasons that it will move on to the living wood. For untreated damp timber however, the Wet Rot fungi is certainly not something you want spreading around your house. There are other Coniophora species, of course – about 20 of them, although Laessoe and Peterson’s 2-volume Fungi of Temperate Europe details just four. The one other I’ve encountered that I was able to identify with any real conviction was Coniophora olivacea, where the greenish brown colour was darker and spread more evenly across the surface, although it still possessed the tell-tale webby edges that formed distinctive threads.

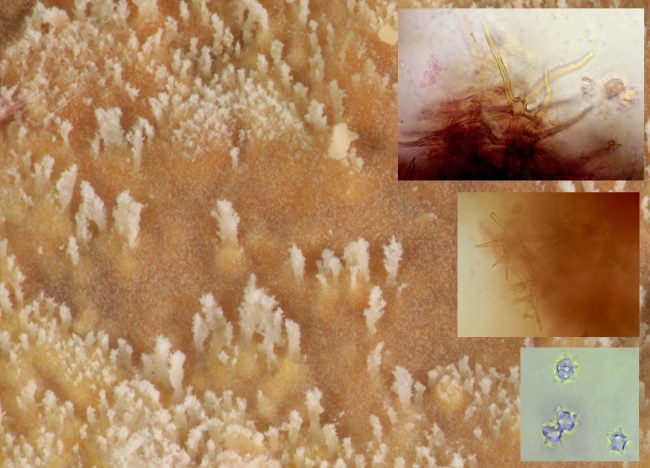

Close up : one can see that Coniophora olivacea has a fuzzy appearance to its surface although shares the same white weblike or fimbriate margins

This one had a perceptible fuzzy-felty appearance, however, and getting much closer with the camera lens, the continuum between its macroscopic and microscopic features became clear to see. Laessoe and Peterson note the “crystal-covered cystidia” as a key feature for Coniophora olivacea (alas, a fungi with no common English name it seems). Cystidia they define as the sterile, well-differentiated surface cells found in all basidiomycetes fungi – on the surface of crust fungi but also in the gills of mushroom shaped fungi – and their size and shape play a key part in the identification of resupinates in particular. Coniophora olivacea is the only species in this genus to have them at all. They are long and finger-like and covered in small granules.

The fuzzy surface of Coniophora olivacea is due to its crystal-encrusted cystidia while its body is also made up of hyphae with simple septa

This relationship between the microscopic structures of crust fungi and their surface appearance is even more striking in the final species I wish to discuss this month, the Fawn Starweb (Asterostroma cervicolor). There are probably not many of us whose curiosity would be aroused by the appearance of a spreading fungal crust on their garden shed, but when I first notice a creamy yellow growth spreading across one of the damp planks closest to the ground following a spell of heavy rain back last August, my first thoughts were to look much closer. I was initially unable to get any closer to revealing the mystery of what species it was due to finding little in the way of distinctive features under the microscope. As it continued to flourish into November, I decided to take a second stab.

A cream yellow crust fungus with white margins growing on a garden shed was revealed to be Asterostroma cervicolor or the Fawn Starweb

A close look at a cross-section immediately revealed a key feature that allowed me to move in straight away – these were the Asterosetae, the peculiar star-shaped structures in the spore-releasing hymenial surface that define it as being a member of the Asterostroma genus (in fact this is what the Latin name means – ‘star body’). Although it is not exactly clear what function these Asterosetae have, their presence meant that this particular specimen couldn’t in fact belong to any other genus. Again, like the previous example of Coniophora olivacea, an intense closeup using a macro lens on a standard camera revealed the tiny crystalline like growths of its otherwise smooth and waxy surface.

A close up of the hymenial surface of the Fawn Starweb hints at the tell-tale structures that comprise it such as the microscopic asterosetae that define it as an Asterostroma species while its small warted spores are also highly distinctive

This is where things got confusing however, as of the 20 odd described Asterostroma species, the scant literature I had at hand only listed two: Asterostroma laxum and Asterostroma medium. The spherical warty spores (which turned blue using the Meltzer’s reagent chemical test) zeroed me in on Asterostroma medium in Hugill and Lucas’ book, which they list as having the synonym Asterostroma cervicolor – the ‘cervicolor’ literally translating to ‘fawn-coloured’ and leading to the rather poetic English common name, the Fawn Starweb, a.k.a. Brown Starweb (actually Hugill and Lucas list the synonym as Asterostroma cervicola, which I assume is a typo rather than another seperate species). I note all this not so as to confuse the reader, but to highlight my own confusion, a confusion that is undoubtedly shared by many delving into the increasingly cryptic field of mycology where even Latin names of species change frequently, new seemingly identical looking species are regularly discovered or reclassified, and very few people outside of specialist cliques have the means, the resources, the knowledge base or the inclination to attempt to identify them in the first place.

The Fawn Starweb may be rarely recorded in the wild but perhaps it is more common in domestic settings.JPG

Though the Fawn Starweb must be common or distinctive enough to have earned itself the right to an English common name in the first place, Hugill and Lucas describe it as “very rare” in the UK. That said, the CATE [Fungus Conservation Trust database] reveals it has been much more commonly recorded in the UK than last month’s fungal discussion point, Antrodia carbonica. Nevertheless, how prevalent it is across other parts of the world is unclear. More confusion emerged, as Hugill and Lucas lists its substrates as “on fallen branches of beech”, whereas the garden shed is obviously not made of beech, but presumably some sort of softwood timber, and no doubt imported too, again highlighting, like the Ash Dieback fungus, the potential pitfalls of moving living or dead wood across national borders. This leads me to think that while A. cervicolor might be considered “very rare” in any sort of “natural habitat” in the UK, it seems to be a lot more common than I initially suspected – numerous websites claim it is one of the less common of the timber decay fungi found in buildings, so like Wet Rot and a number of other rotters, could we consider it a domesticated species?

This Fawn Starweb perhaps revealing the limitations and pitfalls of a plastic lawn

I should also add that the shed itself is set on a plastic lawn (not by my choice!), and it is probably due to the resulting drainage issues that its timber is constantly damp enough to provide a suitable home for wood-rotting fungi. The Fawn Starweb, which is still there as I write this over six months later, even started creeping across the lawn and on to the fence next to the shed proving, as if any further proof is really necessary, that not only do plastic lawns not solve the problems they purport to solve, they cause others too.

Coniophora olivacea

Food for thought anyway. I would hesitate, though, to apply for any special protected status for my garden shed due to it hosting a species considered rare in the wild. In fact, very shortly after I identified it under the microscope last Autumn, I noticed a pair of workmen on the roof of the neighbour’s extension sucking their teeth and muttering something about rotten timber. It looks like this species might be getting quite a bit more common in my local area at the very least.

Comments are closed for this post.

Discussion

I have just discovered Asterostroma cervicolor at Sandpit Copse, Goodwood VC13 West Sussex. 6 October 2022. Submitted on iRecord. I’m 79 years old and quietly looking at fungi for many years with several very rare records. I have not seen the genus Asterostroma previously and am not aware if this species [A. cervicolor] is the first record for vc13.

Thanks for your comment, Howard.

It’s really interesting – I suspect species such as Asterostroma cervicolor are a lot more prevalent in the UK than the number of records suggest, but unless one knows what is looking at, and in this case one needs a microscope to do that, then such things generally tend to go unnoticed!

Jasper

7 November, 2022