April’s Monthly Mushroom : Coral Slime (Ceratiomyxa fruticulosa)

These monthly posts have endeavoured, as much as possible, to focus on a particular mushroom, toadstool or other fungal organism of interest that might be in season around the time they appear online. This means we have now reached a potentially tricky time of year. “March comes in like a lion, and goes out like a lamb”, as the saying goes.

A few weeks ago, when it was still cold and wet, I had considered looking at a number of jelly fungi that I was still finding oozing from damp stumps and fallen trunks, or maybe one of the brackets still hanging on from Winter. Then after the incongruously meekly-named Storm Kevin brought a hail of dead twigs and branches down to ground level for closer inspection, I thought about zooming in to meditate more fully on some of the resupinate crust fungi that I found attached to them.

Coral Slime

Now the trees are blossoming, the woodlands abound with bluebells and winter coats have been exchanged for short sleeves. The seasonal change is quite palpable – for the moment at least. In line with predictions in my last blog, postings with attached photographic evidence of morels and St. George’s Mushrooms have popped from various online mycological or foraging-related sources on my social media feeds, but alas for me, I’ve not been lucky enough to find any for myself in my usual locales.

There have, however, also been numerous reported sightings across the UK of a number of organisms that I have chanced upon fairly regularly over the past few weeks: slime moulds!

Coral Slime

I wrote about these exotic but obscure lifeforms a couple of years ago, just prior to beginning these Mushroom Monthly posts. I use the word ‘lifeform’ advisedly. These are not animals, plants, and most definitely not fungi, but belong to the kingdom of single-celled organisms known as Protista.

So April’s Monthly Mushroom is a bit of a cheat, because despite the name, slime moulds have no real kinship with mushrooms nor even fungal moulds. That said, they seem to attract the most attention from mycologists. Most field guides will devote a few pages to the most common three or four of the thousand or so species found worldwide. This seems all the more bizarre when one considers how your typical fungi fanatic pays scant attention to lichens, a complex symbiotic partnership of two organisms of which a significant component is actually fungal (the other is algae).

The obvious reason for this is that slime moulds do look like fungi, and tend to be found in the same types of damp wet environments. It was for this reason that in 1833 the German naturalist Johann Link gave them the name ‘myxomycetes’, or ‘slime fungus’. Around twenty years later, another German, Anton de Bary, coined a new name, ‘mycetozoa’, or fungus animals, after noticing a peculiar quirk about them - They move!

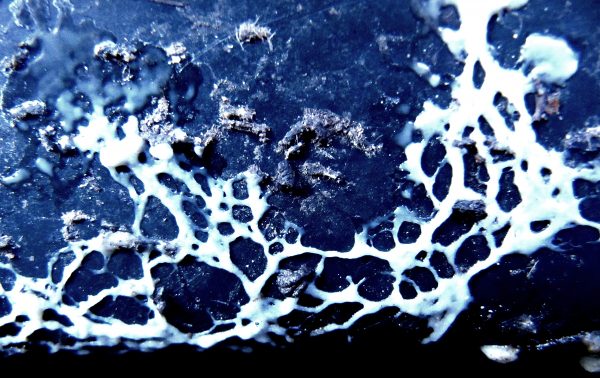

The slimy single-celled cobweb of myxomycetes plasmodium

The terms myxomycetes and mycetozoa are still commonly used today, as is one further term, myxogastria, meaning ‘slimy stomach’, describing the way the organism crawls around its environment hoovering up its food, be it yeasts, bacteria or plant debris. The slime mould, unlike the fungi, is not responsible for decay, but survives off the leftovers. They are not poisonous in any way and, occasionally unsightly appearance notwithstanding, are completely harmless to humans and whatever plant host you might find it upon.

Firstly, let's circumvent one avenue of potential complexity: the slime moulds we are referring to here are plasmodial slime moulds. There are also another class of organisms called cellular slime moulds (Dictyostelium), which are a different entity entirely, but for simplicity’s sake we shall ignore them here.

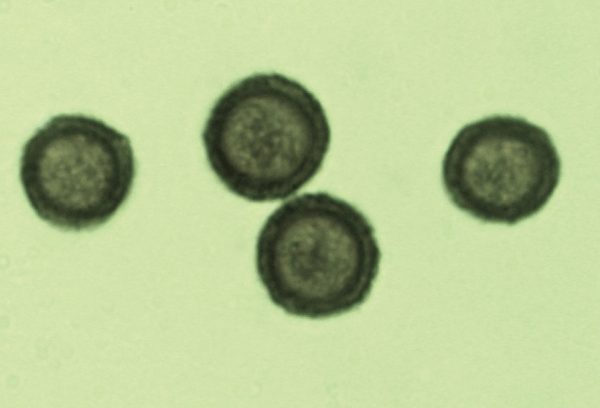

One further peculiarity of the plasmodial slime moulds is that they have four different stages in their life cycle, beginning as spores that then transform into individual microscopic single cells.

Under a microscope, you can identify slime moulds by their spores, such as these from Didymium squamulosum

Then, there is the dramatic part: at some undefined point in their life, presumably related to temperature and moisture levels and availability of food, these swarming disparate cells come together into a single colony, initially forming a network pattern of slime called the plasmodium that efficiently and evenly distributes all the food it absorbs around this cobweb-like “body”. Rather creepily, this plasmodial body is not anchored to one spot but physically moves, both fluidly and pulsatingly, towards its food sources – too slow for the naked eye to perceive, it should be said, but if you found one and came back an hour later, you’d notice the difference.

Plasmodium of an unknown slime mould

At this stage, the plasmodium is effectively still single-celled but multi-nucleate, and in some cases can get up to a vast size, with one single specimen of the Tapioca Slime (Brefeldia maxima) reported as spreading over an entire square metre, making it the largest single-celled organism ever recorded.

Unknown slime mould plasmodium fusing to form fruiting bodies

The next phase is when the plasmodium coalesces and hardens to develop its reproductive bodies, from which the spores are released for the next iteration of this as life cycle. These fruit bodies provide the primary key to identifying the various species, albeit necessitating a microscope for some of the more similar-looking types. There is no way of visually identifying a slime mould by its plasmodium alone.

Tiny fruitbodies of Didymium squamulosum on leaf

For most slime moulds, these fruit bodies are tiny. Many form little pinhead like stalks less than a millimetre or so in height, which you’ll need a magnifying glass or camera macro-lens to examine properly. They grow in groups, sometimes forming clusters of couple of centimetres in diameter, occasionally spreading to a metre or more, depending on the type.

They range in colour, shape and texture, like the miniscule Didymium squamulosum, whose round to discoid heads where the spores are held (the sporangia if we want to get technical) are covered in tiny lime crystals, or the bright yellow feather dusters of some Arcyria species, or the pink sausages on black hair-like stalks of certain Stemonitus.

Stemonitis species growing in dense clump of sporangia

I think it is fair to say most people would walk past slime moulds without even noticing they were there, yet alone giving them a second glance. A handful, however, are large, striking and frequent enough to have earned common English names (Dog Vomit Slime being the most famous!), and two of these in particular seem to be out in force at the moment.

False Puffball slime

The first of these is the False Puffball (easier to remember than either of its Latin names of Reticularia lycoperdon or Enteridium lycoperdon), which is easily spotted due to its solitary fruit body reaching up to 10cm across and looking like, as per its name, certain types of puffball – or perhaps somewhere more between a Ping-Pong ball and a marshmallow. It is slightly atypical for a slime mould in that its spores are all contained within this shiny, slightly pink-tinged membrane, which bursts asunder to release the spores when it is good and ready.

The other unusual type is even more splendid to behold. This is the Coral Slime (Ceratiomyxa fruticulosa). Again, the reason for the English name is obvious. The plasmodium of this one develops into gelatinous spore-bearing structures like star-shaped tentacles that resemble terrestrial Sea Anemones. Michael Jordan in The Encyclopedia of Fungi of Britain and Europe (2004) describes them as “colonies of minute, fragile, whitish, club-shaped bodies arranged in rosettes”, with a “fruiting body up to 10cm dia.”

coral on log

One of the interesting things about slime mould plasmodium is that it will fuse together with other colonies of its own species, so it is difficult to know where one begins and one ends. The Coral Slime is often found spreading across fairly large areas, covering whole logs or tree stumps as in the photo here. The other point is that this near entire translucent white branching fruiting surface is very soft and gelatinous and indeed, watery, to the point where it is very easily squashed if you try to touch it or pick off a sample.

You will need to get pretty close up to appreciate the alien beauty of this in its frost-like fruiting stage, which is unusual even by slime mould standards. As Steven Stephenson notes in Myxomycetes: A Handbook of Slime Moulds (2000), “the fruiting body consists of numerous simple or variously branched and anastomosing [i.e. networked or connected] columns, with the spores borne individually on threadlike stalks”.

Coral slime with spore hairs and associated insect

Looking really close up in this photographic detail, you can see that the tentacles here are covered in tiny hairs, which individually hold a single spore. As Stephenson details, “the spores are not enclosed within the fruiting body as is the case for all other myxomycetes… and a number of biologists have questioned the relationship of Ceratiomyxa to other myxomycetes.” So, not only is a slime mould not a fungus, but a Coral Slime might not even be a proper slime mould!

There are four different Ceratiomyxa species, but C. fruticulosa is the only one you will find in the UK (or anywhere outside the tropics). Even though it appears quite variable in its shape, you are unlikely to mistake it for anything else.

Coral Slime

Slime moulds are infinitely intriguing organisms, and all the more so because so little is known about them. How, for example, does a single-celled lifeform locate and orientate itself towards its food source? How long can we say an individual slime mould lives for, if their repeated lifecycles see them growing, dispersing, coming together then growing again, in an asexual reproductive cycle that goes on ad infinitum?

The unexpected beauty of a slime mould in extreme close up

Slime moulds in general can be incredibly photogenic close up and attract a devout cult of amateur specialists, as is evidenced by specialist Facebook groups such as ‘Slime Mold Identification & Appreciation’, ‘The Slime Mould Collective’ and ‘British Slime Moulds (Myxogastria)’. However, scientific attention to their behaviour, utility and purpose has been limited, which is one of the reasons I worked on The Creeping Garden documentary, a portrait of fascination and obsession fusing the worlds of art and science made with filmmaker Tim Grabham, and a tie-in book about them a few years back.

However, one major advantage myxomycetes have over fungi for those curious nature lovers with a penchant for the really wild side, is that they appear throughout the entire year, so presumably their lifecycles are much more regular than annual. Warm and wet is how most seem to like it, although presumably it varies from species to species. I don’t think there’s much in the way of this kind of information about individual types out there other than the anecdotal. There are a few expensive specialist tomes covering all of the known species around the world, but really the aforementioned book by Stevenson is the only affordable beginners guide.

It is funny to think that this wasn’t always the case. Over a hundred years ago, Gulielma Lister (1860-1949), scion of the great antiseptic dynasty and one-time president of the British Mycological Society, had assisted and then taken over from her father Arthur Lister’s work in compiling and illustrating such works as A Monograph of the Mycetozoa, published by what is now the British Natural History Museum in 1894.

In the new edition of Guide to the British Mycetozoa Exhibited in the Department of Botany British Museum (Natural History), published in 1909 following her father’s death the previous year, Gulielma had already detailed much of what we currently know about the Coral Slime, for example, observing that it has “a slender stalk bearing a single ellipsoid spore”. Meanwhile in the later The Mycetozoa: A Short History of their Study in Britain; An Account of their Habitats; and a List of Species Recorded From Essex (1918), she writes “If the timber is much decayed, it will often produce, in summer time, sheets of the fleecy sporophores of Ceratiomyxa”, noting that the species of our focus for April is “abundant on decayed logs and stumps; appearing from June to September, and rarely, in October.”

I found a Coral Slime in early December 2018, and another in mid-March, and have also recently seen on the internet quite a few further reported sightings of them cropping up all over the country – further proof, perhaps, that our concepts of the season are quite different than they were a hundred years ago.

Comments are closed for this post.

Thank you so much for this article! I’ve taken a few photographs of various growth stages of this fungi in the New Forest [Dibden Inclosure], and I couldn’t for the life of me figure out what it was, as it wasn’t in any books I had.

I thought it looked like a sea anemone or coral close up, so I’m glad I finally managed to find the right google criteria for this to pop up!

It’s a beautiful fungi!

Lotus B. Lazuli

22 December, 2020